Dogs are enduring runners, excellent hunters, and loyal companions. But what exactly makes them so special? Let’s explore their body structure from a scientific angle and discover some fascinating facts.

Why study a dog’s body structure?

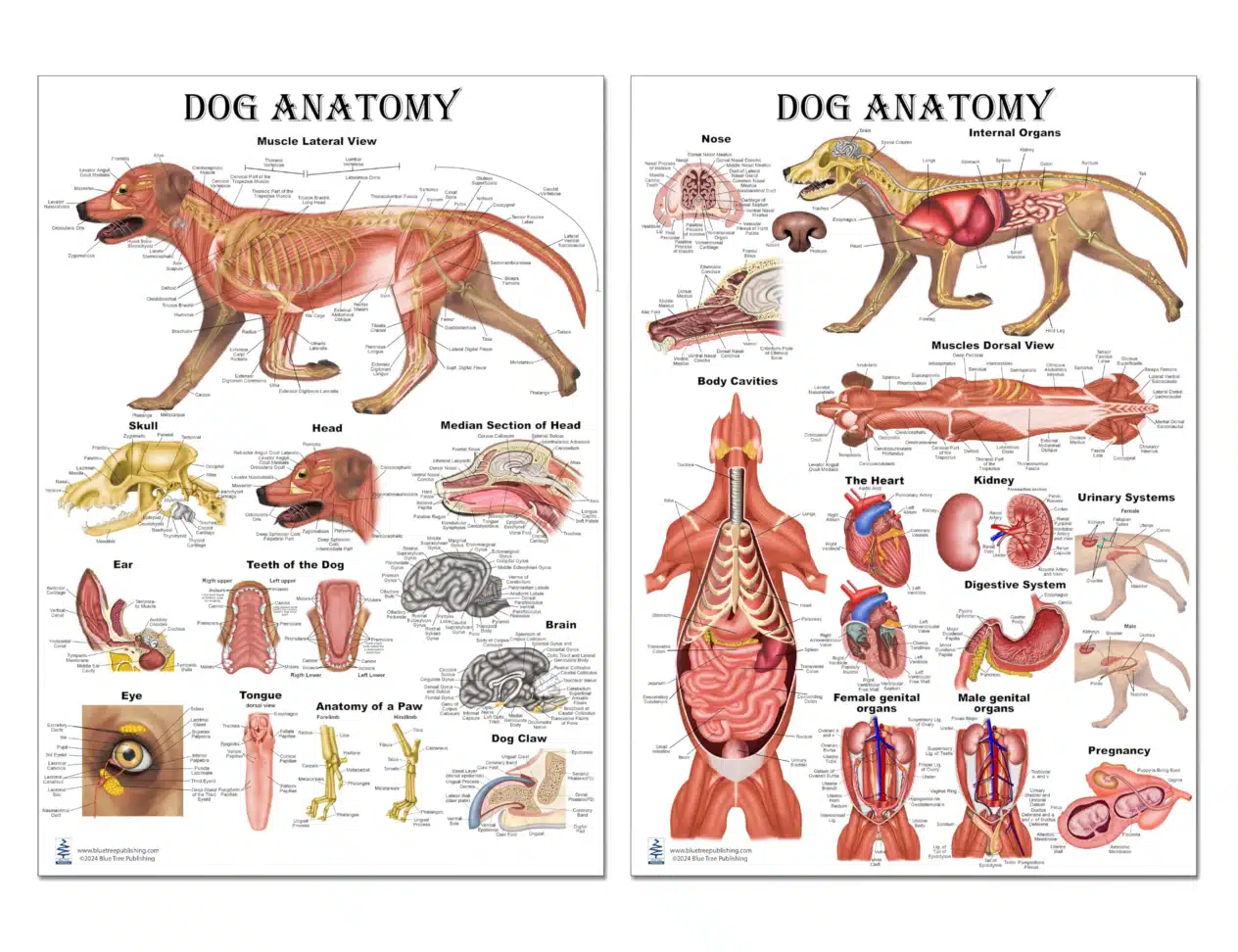

Canine anatomy is the key to understanding behavior, physical capabilities, and health. Knowing how the body is built helps with care, veterinary treatment, and grooming. For example, understanding the skeleton, muscles, and coat allows for appropriate exercise, diet, and care. Dogs with short legs, like Dachshunds, need gentle handling of the spine, while large breeds require joint support. In veterinary medicine, knowledge of internal organs helps detect diseases early. Brachycephalic breeds like Pugs and Bulldogs, for instance, may have breathing issues due to their short snouts — an important factor during treatment. In grooming, skin and coat features influence the choice of procedures. Some breeds have coarse hair that requires hand-stripping, while others have skin prone to dermatological conditions.

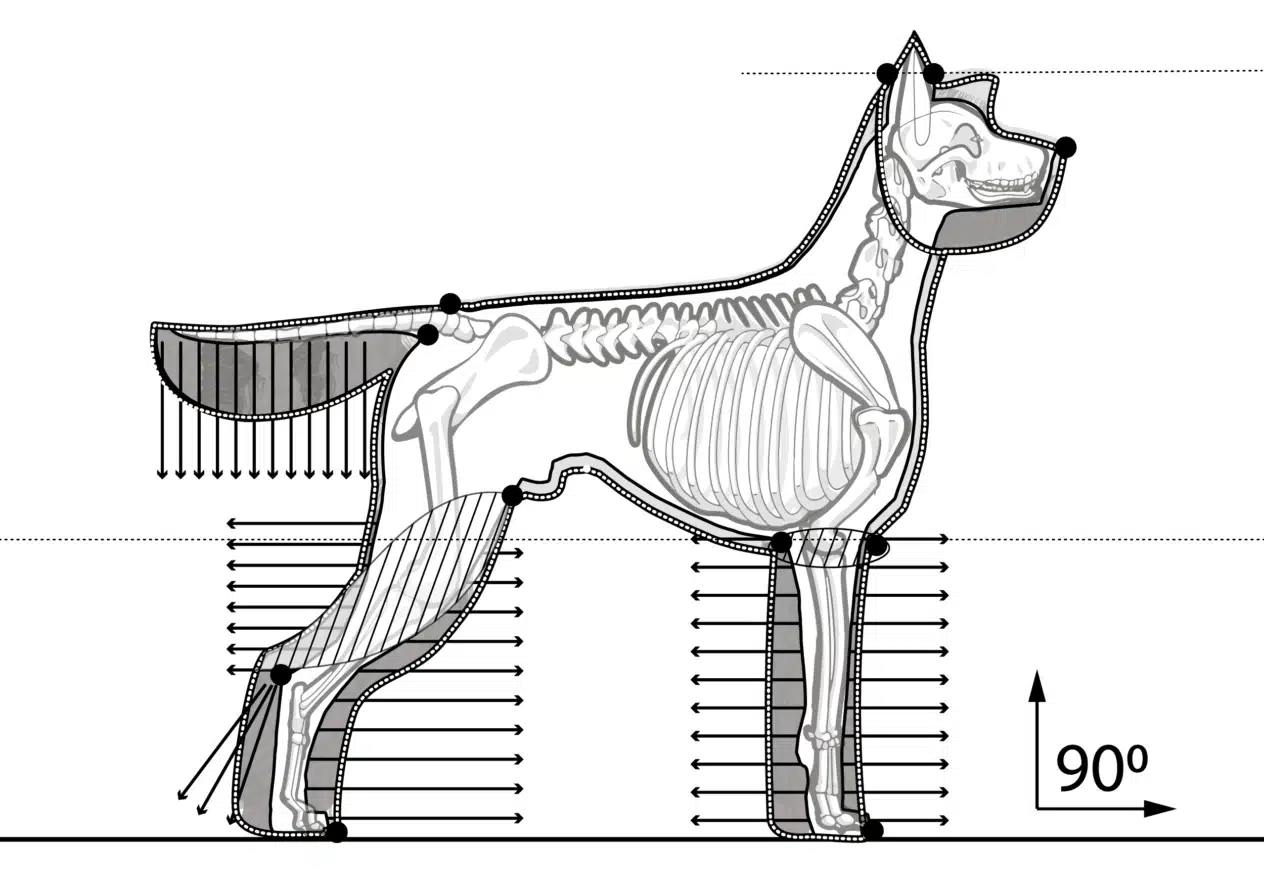

Skeletal and muscular system: the foundation of movement

A dog’s skeleton forms the framework that provides endurance, flexibility, and speed. Depending on the breed, dogs have between 230 and 319 bones, compared to just 206 in humans. Their flexible spine, aided by well-developed intervertebral discs, allows for remarkable agility — enabling quick turns, jumps, and dodging obstacles. One unique feature is the near absence of a collarbone, giving the front legs greater freedom of movement and allowing for smoother, faster running. The front limbs have a sturdier bone structure, as they bear most of the body weight, while the hind limbs are responsible for propulsion during motion.

A dog’s jaws are a true survival tool. Powerful chewing muscles allow them to grip prey or gnaw through hard objects. In some breeds, especially fighting breeds, the jaw strength can reach up to 200 kg of pressure. Their teeth are specialized: sharp canines are used to tear food, while premolars and molars help crush bones and meat. With more bones than humans — between 230 and 319 — and a missing collarbone, dogs are built for highly agile and efficient movement.

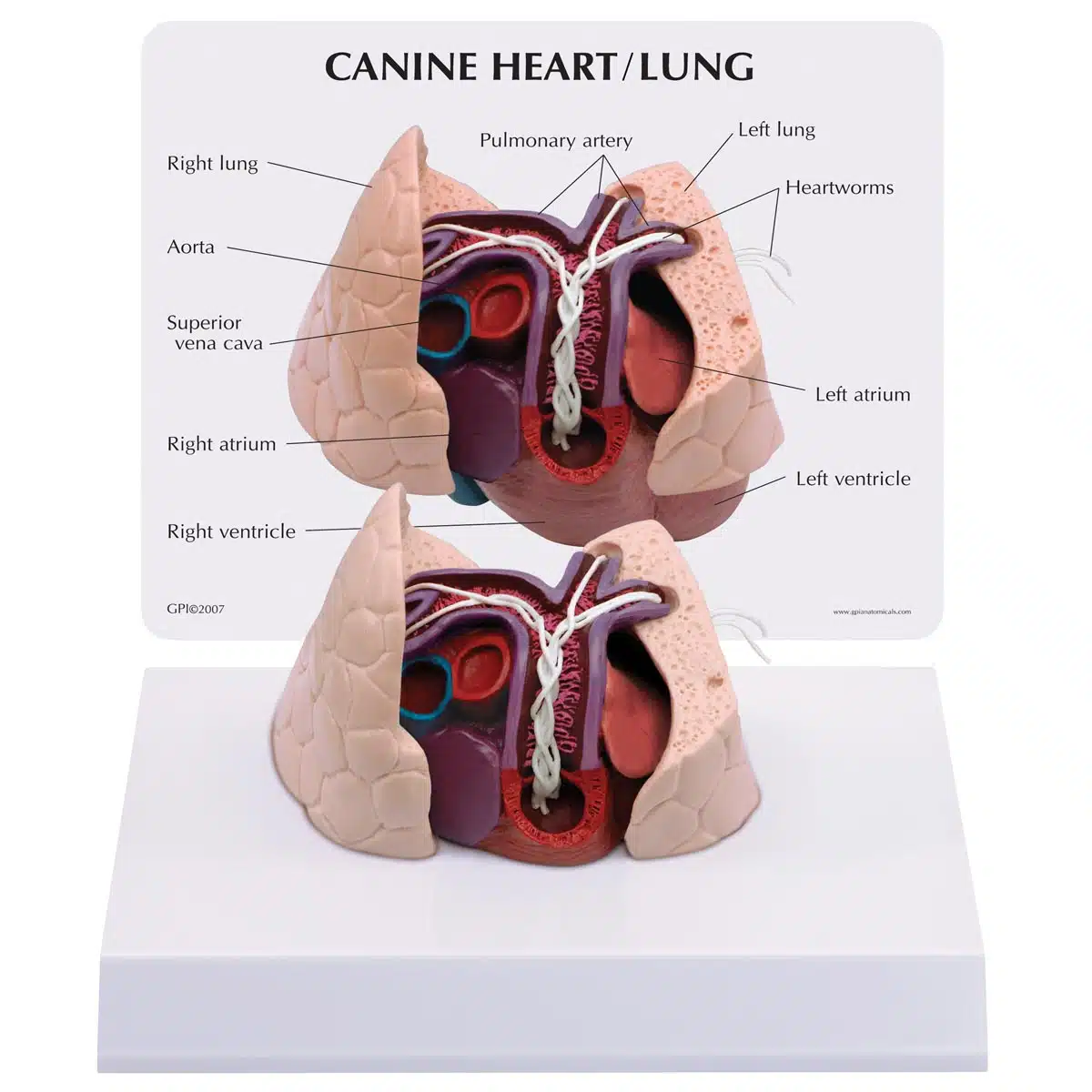

Respiratory and cardiovascular system

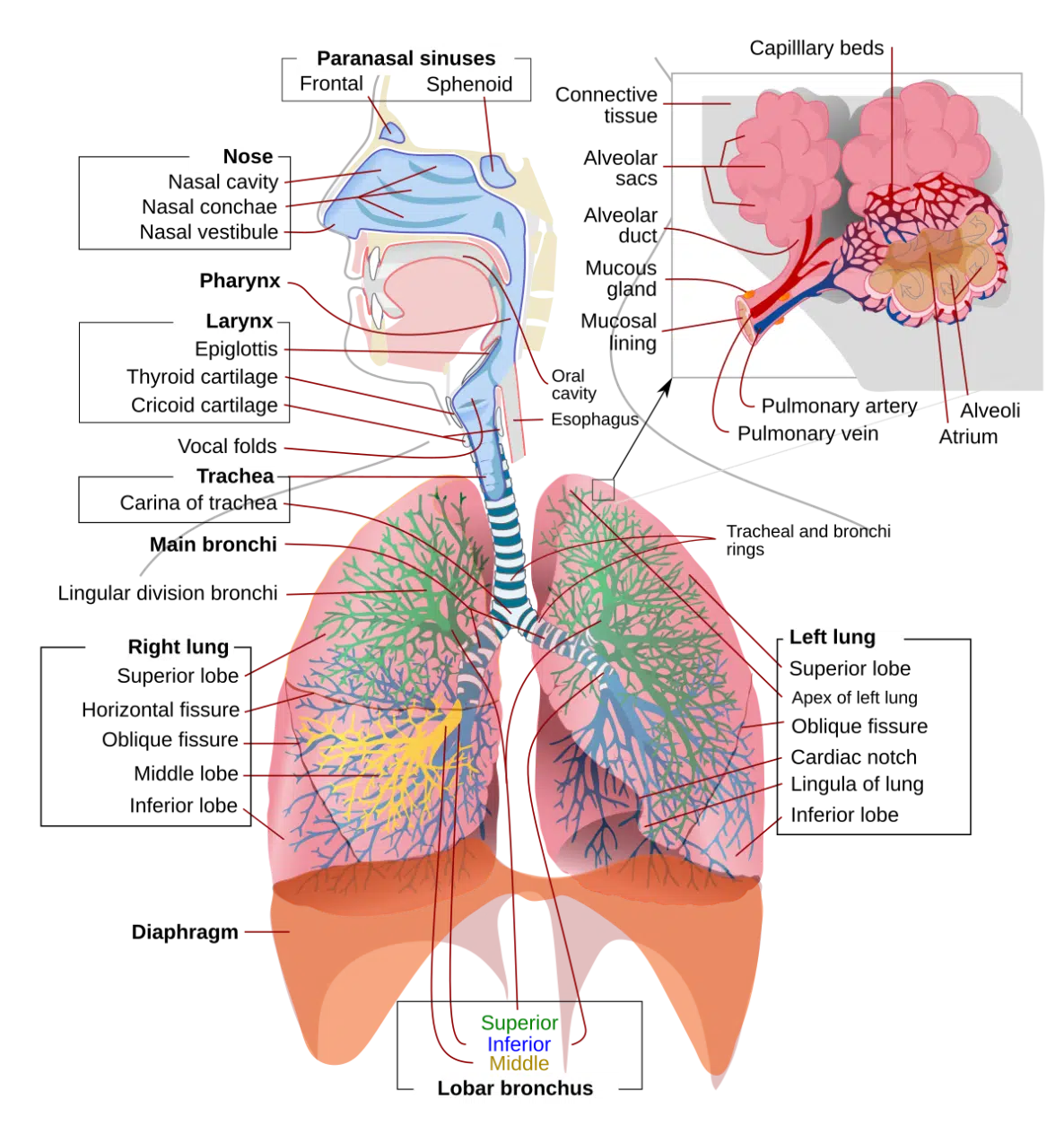

To maintain high levels of activity, dogs have a well-developed respiratory and cardiovascular system that allows them to quickly oxygenate their blood. Their respiratory system is designed not only for efficient gas exchange but also for cooling the body. As air passes through the nose, it gets filtered and adjusted to the ambient temperature. The lungs quickly absorb oxygen, enabling dogs to remain physically active for extended periods.

A dog’s heart is relatively large in proportion to its body mass and beats faster than a human’s. Heart rate varies by breed size: in small dogs, it ranges from 100 to 140 beats per minute, while in medium and large breeds it ranges from 60 to 100. This rapid circulation allows for quick recovery after exertion.

Unlike humans, dogs have very few sweat glands. Their main method of thermoregulation is panting. When a dog breathes with its tongue out, moisture evaporates quickly, helping to cool the body. This is why dogs pant more during hot weather — it’s an essential mechanism for lowering their body temperature.

On average, a dog’s heart beats between 60 and 140 times per minute — noticeably faster than in humans. And because they barely sweat, dogs rely on panting to keep cool.

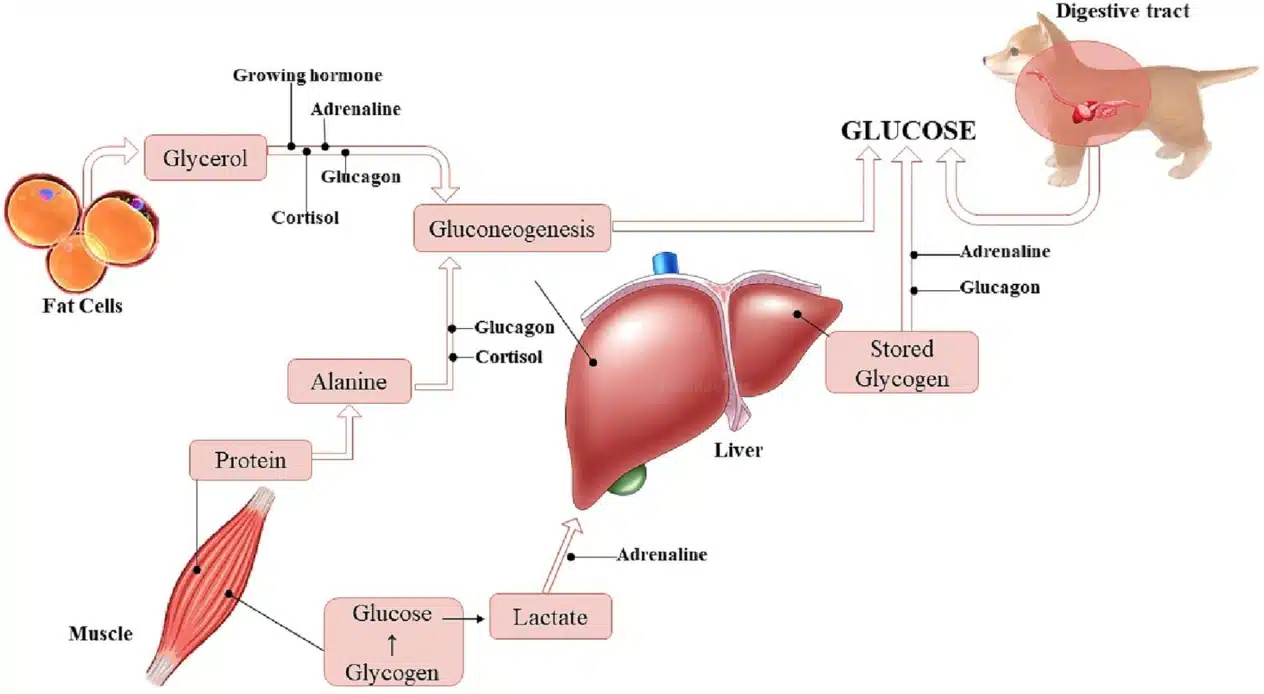

Digestive system and metabolism in dogs

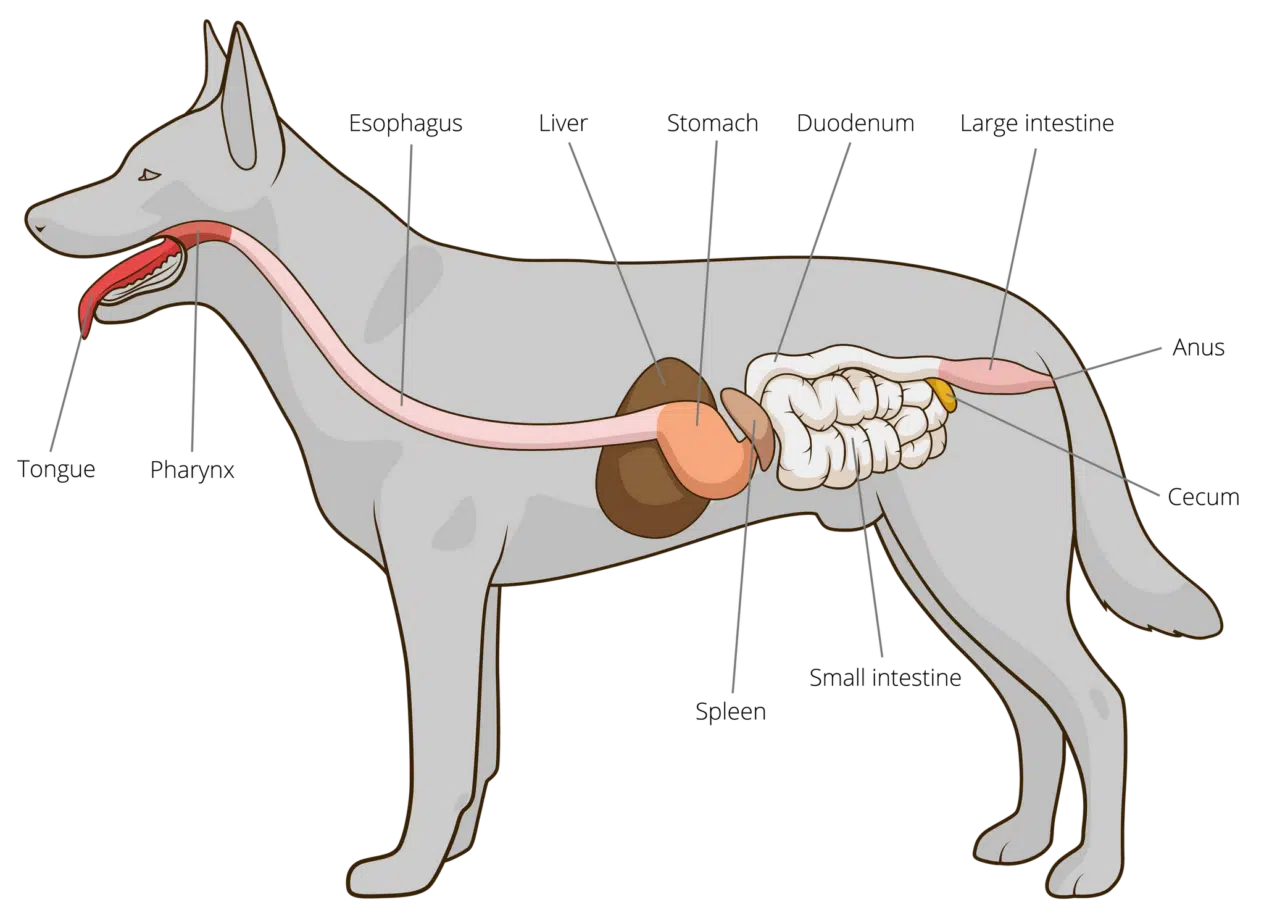

A dog’s digestive system is adapted to efficiently process meat and other animal-based foods. The main digestive organs include the esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, as well as the liver and pancreas, which play vital roles in breaking down and absorbing nutrients.

The dog’s stomach is a powerful chamber with an extremely acidic environment (pH between 1 and 2), which allows them to digest even bones by dissolving them into a safe form. Unlike humans, whose digestion begins in the mouth, dog saliva lacks enzymes for breaking down carbohydrates and serves primarily to moisten food before swallowing.

A dog’s intestines are significantly shorter than those of herbivores — and even shorter than in humans. This allows food to move quickly through the digestive tract, reducing the chance for harmful bacteria to multiply and cause infections. That’s why dogs can safely consume raw meat, while humans cannot. Their digestive systems are geared toward processing protein-rich food rapidly, whereas the human system is more suited to digesting plant matter.

📌 Fun facts:

✔️ Dog saliva contains antibacterial compounds that help wounds heal.

✔️ The acid in a dog’s stomach has a pH of 1–2 — strong enough to digest even bones.

Smell, vision, and hearing: how dogs perceive the world

The world looks entirely different to a dog than it does to a human — it’s full of smells and sounds, with vision playing a lesser role.

Smell is a dog’s most important sense. Their olfactory system is far more advanced than ours, with around 300 million scent receptors compared to only 5 million in humans. They also possess a special organ — the vomeronasal organ (or Jacobson’s organ) — which detects pheromones. This means dogs can not only pick up ordinary scents but also gather information about the emotional or physical state of animals and humans. That’s why they can often sense anxiety or illness in their owner before any visible symptoms appear.

Dog vision has its own unique features. While they don’t see colors as vividly as humans, their eyes are adapted for low-light conditions. Their retinas have more rods — cells responsible for light sensitivity — and they possess a reflective membrane called the tapetum, which bounces light back through the retina and enhances night vision. This is also why their eyes may appear to glow in the dark.

Dog hearing is incredibly sensitive. They can detect sounds in the range of 40 Hz to 60,000 Hz, while the human range tops out at 20,000 Hz. This enables them to hear ultrasonic signals we can’t detect. Moreover, dogs can move their ears independently, helping them pinpoint the direction of a sound with great accuracy — even from a distance.

📌 Fun facts:

✔️ Dogs can detect scents from several kilometers away.

✔️ Their eyes contain more rods, making them better at seeing in twilight conditions.

✔️ Their ears can move independently to catch sounds from all directions.

A dog’s anatomy is a remarkable blend of natural mechanisms designed for survival, adaptation, and communication. Their powerful sense of smell, keen hearing, and enhanced night vision have evolved over thousands of years, making them ideal companions, hunters, and guardians.

Skin, coat, and thermoregulation in dogs

Thermoregulation in dogs functions very differently from that in humans. Dogs hardly sweat at all and rely on other mechanisms to maintain a stable body temperature. The main components involved are the coat, paw pads, and specialized glands.

Why do dogs only sweat through their paw pads?

Unlike humans, dogs have very few sweat glands, which are found only on the paw pads and serve a minor cooling function. When the ambient temperature rises, dogs release a small amount of sweat through these glands to slightly cool their paws. However, their primary method of cooling is panting with the tongue out, which promotes evaporation from the mucous membranes — a highly effective way to reduce body temperature.

Interestingly, between their toes, dogs have specialized apocrine glands that not only assist with thermoregulation but also emit a unique scent. That’s why dogs often scratch the ground with their paws after relieving themselves — they’re leaving behind both a visible trace and a personalized scent marker.

Thermoregulation in dogs functions very differently from that in humans. Dogs hardly sweat and instead maintain a normal body temperature through other means. The main roles in this process are played by their coat, paw pads, and specific glands.

Why do dogs only sweat through their paw pads?

Unlike humans, dogs have very few sweat glands, and those are located only in their paw pads, serving an auxiliary function. When the temperature rises, dogs release sweat through these glands to slightly cool the paws. However, the primary method of thermoregulation is not sweating but rapid panting with the tongue out, which causes moisture to evaporate from the mucous membranes.

Interestingly, between the toes, dogs have special apocrine glands that not only help with thermoregulation but also release an individual scent. That’s why dogs often scratch the ground with their paws after relieving themselves — they’re not just leaving a mark, but also their unique scent.

How does a dog’s coat protect from heat and cold?

A dog’s coat is a natural mechanism that performs multiple functions: it protects against cold, heat, moisture, and even mechanical injuries. In many breeds, it has a double-layered structure: the outer coat is made of coarse guard hairs that repel water and protect against damage, while the undercoat is thick and dense, helping retain heat in winter and prevent overheating in summer.

Many people mistakenly believe that long-haired dogs feel overly hot in summer and try to shave them completely. In reality, this can be harmful. The dense undercoat creates an insulating air layer that blocks hot air from reaching the skin in summer and retains warmth in winter. Shaving off the undercoat can lead to sunburn and even overheating.

📌 Fun facts:

✔️ Dogs have special glands between their toes that help leave a unique scent.

✔️ Some breeds have a double coat that protects them from both heat and cold.

Conclusion

Dogs have a flexible skeleton, a strong muscular system, and sharp teeth and jaws that help them survive in a wide range of environments. Their senses are far more developed than those of humans: their sense of smell detects the faintest odors, their hearing perceives ultrasonic frequencies, and their eyesight is adapted to low-light conditions.

Thermoregulation in dogs is fundamentally different from that of humans. They hardly sweat and cool themselves through panting and specialized glands on their paws. Their coat protects them from both heat and cold and plays a crucial role in their overall anatomy.

Understanding a dog’s anatomy is useful not only for veterinarians, groomers, or trainers, but for all pet owners. It helps in providing better care, selecting an appropriate diet, offering the right physical activity, and avoiding common mistakes that may affect a dog’s health. The more we know about how dogs are built and how their bodies work, the better we can ensure they live healthy, happy, and comfortable lives by our side.

THANKS FOR THE INFORMATION

You’re welcome! Glad you found it helpful. If you have any more questions, feel free to ask!